This essay began as just a list of links I wanted to share, so that’s why it’s so heavy on them. I found myself wanting to connect the tissue between them, and here we are.

I took a break from my Apple Watch for a little while to see how I was without it. I found myself going back pretty fast. Just a few weeks ago, I wrote: “The main thing I’m taking away from my experiment is that I’m not very motivated by myself. I work well with deadlines and budgets, with Apple Watch goals, with people expecting something of me. I don’t do much if I’m alone.” I found myself missing the gamification of health, because—surprise—they succeeded in making me addicted to the points.

A friend of mine sent me this podcast about keeping streaks. The guest, Jackie Silverman, mentioned “I believe in a pilot study we ran, we asked about 100 people online, how many name apps that you use that record their streaks. And they named about 200 unique apps. So this is a super common thing.” This stuff is everywhere. It’s extremely common in every kind of service. And streaks are just one kind of gamification.

Gamification’s whole thing is about adding game elements like points, streaks, and badges to help make not fun things into more fun things. What it actually seems to do is it make an activity you’d rather not do slightly more addictive. Cory Doctorow, as usual, gets that: “The important thing about a game isn’t how fun it is, it’s how easy it is to start playing and how hard it is to stop” (For the Win). So many modern apps and a lot of video games are designed with not necessarily a fun game loop but an addictive gamified loop. This sucks for the player, because they’re a) now addicted to something they weren’t before, b), probably losing real money to it, and c) not even having a good time.

The people writing Slime Mold Time Mold have been working on a very long essay about….well, a lot of things. But some of it is about our obsession with “value” and rewards that leads us astray. The “builder’s mindset,” according to one of them, gets stuck “building a mind around notions of ‘value’ quickly leads you into contradictions…Governors clearly learn how actions change the world, not whether or not they are ‘valuable.’ There is no reward and no punishment” (The Mind in the Wheel – Part IV: Learning). Instead of focusing on real outcomes—like actually speaking a language comfortably or enjoying a great game—we’re given streaks and badges as substitutes for genuine progress or joy.

Language learning apps like Duolingo are the worst offenders of this, obviously. Please read this article by Caitlin Dewey, where they come to this: “If your goal is to learn a language in the most efficient way possible, you’d be better off using something other than Duolingo,” and just as damning, “if your goal is to have fun gaming, then you’d be better off finding a game more fun than Duolingo” (When Gamification Goes Too Far).

Here’s where I’m going to break off in a different direction and talk about video gaming itself. I’m coming at this mainly as a perspective as someone who plays and likes them, so gamification means something a little differently to me.

Video games as a medium is unique in that, unlike the consumption of movies, books, or art, you have to press buttons to make the thing go. As Alanna Okun writes: “even the simplest, most mind-numbingly repetitive games need you to actually sit down and play them. It’s a different kind of buy-in than watching a show…” (How to Get Into Video Games).

Video games are also modifiable, either by the developers or by the players. These mods can be in the form of accessibility, improvements, or cheats.

In recent Final Fantasy re-releases, the player gets options in the settings to level up faster than originally designed. Kaile Hultner describes stomping through games grossly overpowered: “Meanwhile, I know I’m not experiencing the games “the way they were meant to be played” simply because I’m ramping up all the boosts, babey. I’m rolling into towns as a Gillionaire and overleveled by a factor of 10”—but concludes the analysis often stops at the shallow “am I having fun?” (Am I Actually Playing Final Fantasy or What?). Sometimes, the answer is yes—but you’re no longer having fun playing the game as it was. You’re playing something else, now.

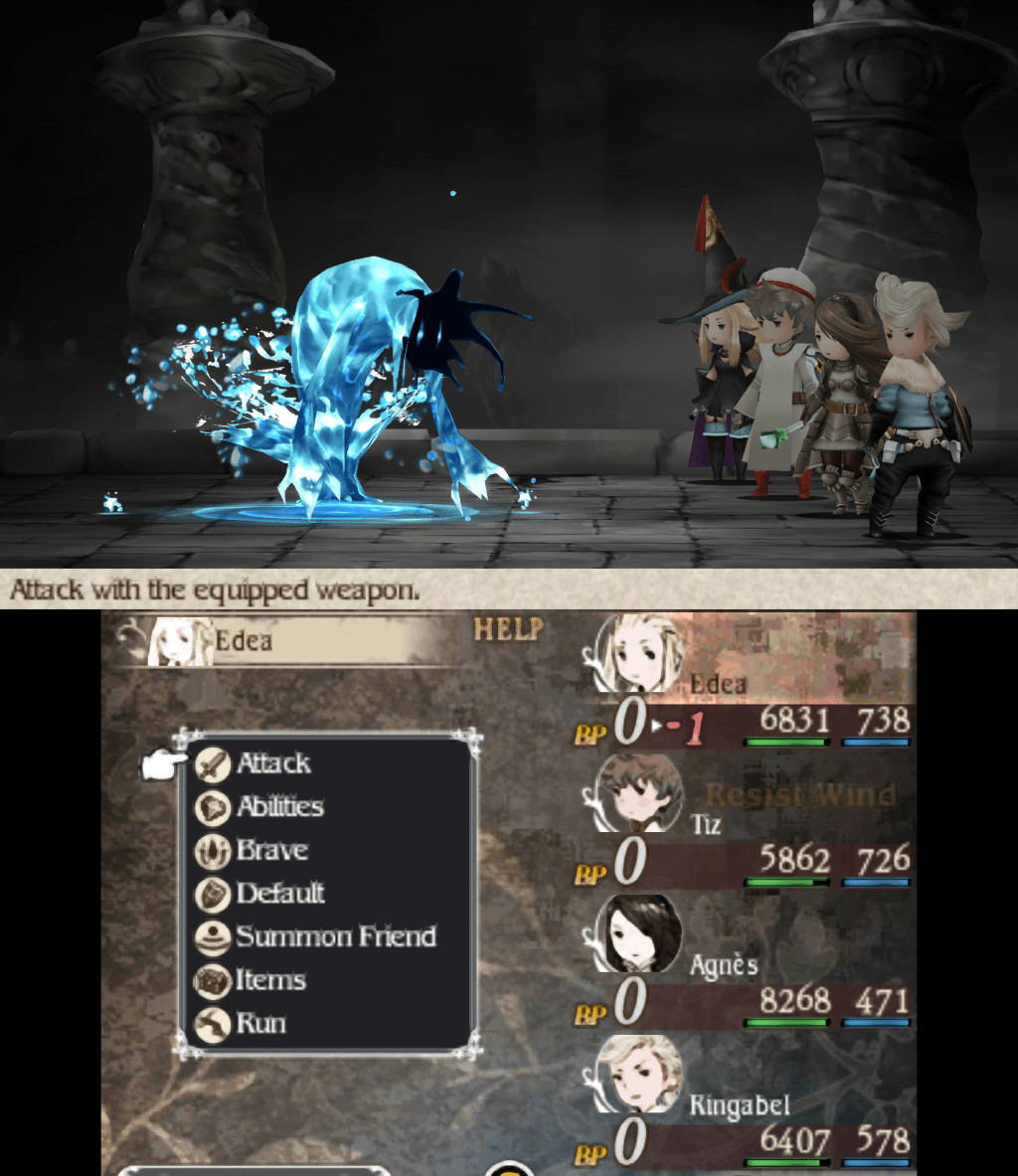

Recently, I re-played the 2012 RPG Bravely Default just like this. After an hour or so of grinding normally, I decided to tweak both the in-game settings and also apply a hack to essentially eliminate the “game” part of it. You can read about that experience here, but I’ll sum up: turning an RPG into a walking simulator/visual novel can be *relaxing*, but it loses so much of the friction of playing a game that it might not stick with me as much of a memory. I also probably optimized the fun out of the game.

And maybe that’s what’s happening with gamification. I’ll repeat what’s in that link in the previous paragraph: “Many players cannot help approaching a game as an optimization puzzle. What gives the most reward for the least risk? What strategy provides the highest chance – or even a guaranteed chance – of success? Given the opportunity, players will optimize the fun out of a game.” (Water Finds a Crack)

Maybe what I’m getting at here is the feeling of gamification as optimization might be interesting as a New Game+ feature but probably a mistake if you’re trying to actually learn something. I love Casey Newton’s essay about productivity and note-taking apps, especially where he lands on optimization: “it is probably a mistake…to ask software to improve our thinking… this will not be enough. It might not even be worth trying” (Why Note-Taking Apps Don’t Make Us Smarter).

It’s also worth noting the emptiness of apps that are engineered for stickiness above all. Something Merlin Mann wrote once still hits me like a truck: “What makes you feel less bored soon makes you into an addict.” (Better.) Good games—and good learning—are not about streaks or badges but about engagement, fairness, and the freedom to fail.

Leave a comment